BORDEAUX WINE VINTAGE QUALITY AND THE WEATHER

Orley Ashenfelter

David Ashmore

Robert Lalonde

"Nor let thy vineyard bend toward the sun when setting"

Virgil

In this paper we show that the quality of the vintage for red

Bordeaux wines, as judged by the prices of mature wines, can be

predicted by the weather during the growing season that produced

the wines. Red Bordeaux wines have been produced in the same place

and in much the same way for hundreds of years. When young, the

wines from the best vineyards are astringent, and many people find

them unpleasant to consume. As these wines age they lose their

astringency and many people find them very pleasant to consume.

Because Bordeaux wines taste better when they are older, there is

an incentive to store the young wines until they are mature. As a

result, there is an active market in young wines (similar to "new

issues" in the securities markets) and an active market in older

wines (similar to the secondary markets in securities).

Surprisingly, the weather information that is so useful in

predicting the prices of the mature wines plays little or no role

in setting the prices of the young wines. We show that young wines

are usually over-priced relative to what we would predict based on

the weather and the price of the old wines. As the young wines

age, however, their prices usually converge to our predictions.

This implies that "bad" vintages are over-priced when they are

young, and that "good" vintages may sometimes be under-priced when

they are young. Rational buyers should avoid bad vintages when

they are young, but they may sometimes wish to purchase good

vintages.

Although the evidence suggests that the market for older wines

is relatively efficient, it implies that the market for younger

wines is very inefficient. Why don't the purchasers of young wines

wait and buy them when they are mature? And why do purchasers

ignore the weather that produced the vintage in making their

decisions? Although there are no simple answers to these

questions, we discuss one possible explanation in the final section

of this paper.

1. Vineyards and Vintages

The best wines of Bordeaux are made from grapes grown on

specific plots of land and the wine is named after the property (or

chateau) where the grapes are grown. In fact, knowledge of the

chateau and vintage provides most of the information about the

quality of the wine. That is, if we imagine 10 vintages and 6

chateaux, there are, in principle, 60 different wines of different

quality. However, knowing the reputations of the 6 chateaux and

the 10 vintages is sufficient to determine the quality of all 60

wines. That is, good vintages produce good wines in all vineyards

and the best wines in each vintage are usually produced by the best

vineyards.

Although this point is sometimes denied by those who produce

the wines, and especially by those who sell the young wines, it is

easy to establish its truth by reference to the prices of the

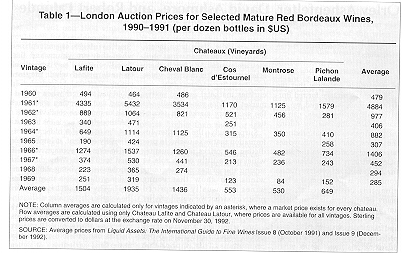

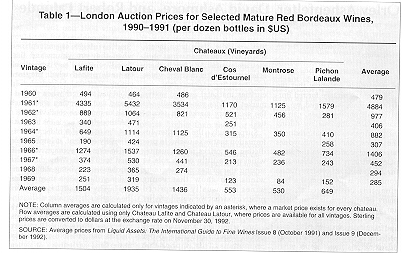

mature wines. To demonstrate the point, Table 1 indicates the

current market price in London of 6 Bordeaux chateaux from the 10

vintages from 1960-1969.

These chateaux were selected because they

are large producers and their wines appear frequently in the

secondary (auction) markets. (A blank in the table indicates that

the wine has not appeared in the market recently. Lower quality

vintages are typically the first to leave the market.) The

vintages from 1960-1969 are selected because, by the 1990s, these

wines are fully mature and there is little remaining uncertainty

about their quality.

From the table it is obvious that knowledge of the row means

and the column means is sufficient to predict most of the prices in

the table. (The explained variance from a regression of the

logarithm of the price on chateau and vintage dummies is over 90%.)

A ranking of the chateaux in order of quality based on their prices

would be Latour, (Lafite, Cheval Blanc), Pichon-Lalande, (Cos

d'Estournel, Montrose). In fact, as Edmund Penning-Rowsell points

out in his classic book The Wines of Bordeaux, the famous 1855

classification of the chateaux of Bordeaux into quality grades was

based on a similar assessment by price alone. Surprisingly, the

1855 classification ranks these chateaux in only a slightly

different order: Lafite, Latour, Pichon-Lalande, Cos d'Estournel,

and Montrose. (Cheval Blanc was not ranked in 1855.) Likewise, a

ranking of the quality of the vintages based on price alone would

be 1961, 1966, (1962, 1964), 1967. The remaining vintages (1960,

1963, 1965, 1968, 1969) would be ranked inferior to these 5, but,

perhaps because of this fact, many of the wines from these inferior

vintages are no longer sold in the secondary market.

2. Real Rate of Return to Holding Bordeaux Wine

It is natural to ask why the prices of mature wines from a

single chateau, made in the same way from grapes grown in the same

place by the same winemaker, would differ so dramatically from

vintage to vintage, as is indicated by Table 1. There are two

obvious explanations for this vintage variability. First, the

older wines have been held longer, and so they must bear a normal

rate of return. This fact alone would make the older wines more

expensive than the younger ones. Second, the quality of the wines

of different vintages may vary because the quality of the grapes

used to make the wines varies.

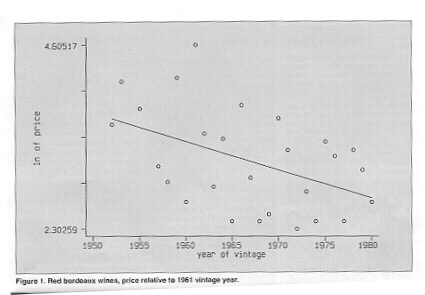

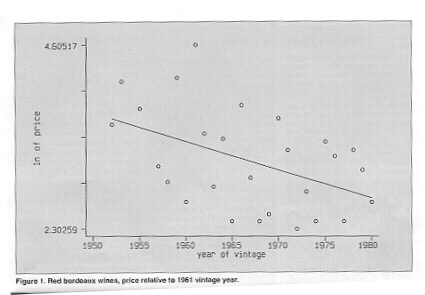

Figure 1 provides a test of the hypothesis that the price of

the wines varies because of their age. In this figure (and

throughout the remainder of the paper) we use as a measure of the

price of a vintage an index based on the wines of several chateaux.

The chateaux are deliberately selected to represent the most

expensive wines (Lafite, Latour, Margaux, Cheval Blanc) as well as

a selection of wines that are less expensive (Ducru Beaucaillou,

Leoville Las Cases, Palmer, Pichon Lalande, Beychevelle, Cos

d'Estournel, Giscours, Gruaud-Larose, and Lynch-Bages).

We

construct the index of vintage price from a regression of the

logarithm of the price from several thousand auction sales on dummy

variables indicating the chateau and the vintages. (The precise

composition of the sample has very little effect on the results.)

The regression coefficients for the vintage dummies are then used

to construct the vintage index. This provides a simple way to

construct a vintage index in the presence of an unbalanced sample

design. (We compute the antilogarithm of these coefficients and

then express the price relative to the index price for 1961. This

is merely a convenient normalization and affects only the intercept

in the regressions reported below.)

Figure 1 is a scatter diagram of the logarithm of the price of

the wines of a vintage against the vintage year. (The vintages of

1954 and 1956 are not plotted, as these wines are now rarely sold.

These two vintages are generally considered to be the poorest in

their decade.) It is apparent from the diagram that there is a

negatively inclined relationship. The slope of the regression line

through these points is -.035. This is an estimate of (the

negative of) what economists sometimes call the real product rate

of return to holding Bordeaux wines. A "real product rate of

return" is a number such that its reciprocal indicates how many

bottles of wine one would have to keep in the cellar in order to be

able to consume one bottle per year in perpetuity. These data

indicate that it would be necessary to have about 28 bottles in a

perpetual cellar that was intended to support the consumption of 1

bottle per year. With a cellar of this size the proceeds from the

sale of the older vintages would be just sufficient to restock the

cellar and provide the consumption of one bottle. Since it is

denominated in bottles of wine rather than dollars, this measure

does not tell us what the return to holding wine denominated in

generalized purchasing power (money) is.

We have analyzed the relationship between the (log) price of

Bordeaux wine and its age for many individual chateaux. So long as

sample includes at least 20 vintages, we invariably obtain a

negative slope to this relationship of around -.03. It is notable

that the study of the various vintages of wine provides so reliable

and simple a measure of the real rate of return. As we shall see,

most of the remaining variation in the price of the wine of

different vintages is due to variation from vintage to vintage in

the weather that produced the grapes.

3. Vintages and the Weather

It is well known that the quality of any fruit, in general,

depends on the weather during the growing season that produced the

fruit. What is not so widely understood, is that in some

localities the weather will vary dramatically from one year to the

next. In California, for example, it never rains in the summer,

and it is always warm in the summer. There is a simple reason for

this. In California a high pressure weather system settles each

summer over the California coast and produces a warm, dry growing

season for the grapes planted there. In Bordeaux this sometimes

happens--but usually it does not. Great vintages for Bordeaux

wines correspond to the years in which August and September are

dry, the growing season is warm, and the previous winter has been

wet.

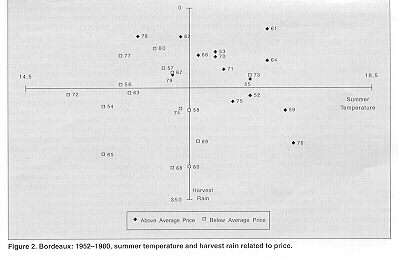

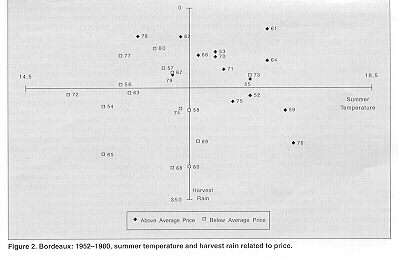

Figure 2 establishes that it is hot, dry summers that produce

the vintages in which the mature wines obtain the higher prices.

This figure displays for each vintage the summer temperature from

low to high as you move from left to right, and the harvest rain

from low to high as you move from top to bottom. Vintages that

sell for an above average price are displayed in dark shading, and

vintages that sell for a below average price are displayed in light

shading.

If the weather is the key determinant of wine quality,

then the dark points should be in the northeast quadrant of the

diagram and the light points should be in the southwest quadrant of

the diagram. It is apparent that this is precisely the case. Even

anomalies, like the 1973 vintage, tend to corroborate the fact that

the weather determines the quality of the wines. The wines of this

vintage, which are of somewhat above average quality, have always

sold at relatively low prices; insiders know that they are often

bargains.

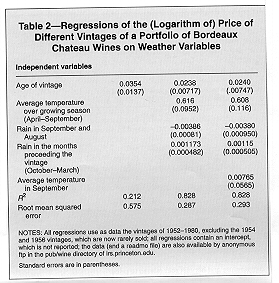

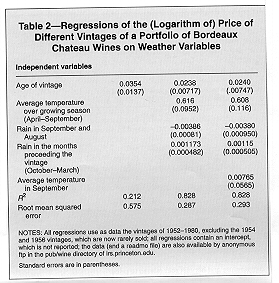

Table 2 contains a regression of the (log) price of the

vintage on the age of the vintage and the weather variables

indicated. In practice, the weather variables are almost

uncorrelated with each other and with the age of the vintage.

As

a result, the regression equation is remarkably robust to the

addition of other variables. The second row of the table contains

the basic "Bordeaux equation," while the third row shows the effect

on the regression of adding the temperature in September as an

additional variable. It is obvious that this variable does not

have a statistically significant coefficient and, indeed, in

further experimentation we have not found any other statistically

significant variables to add to the regression.

As

a result, the regression equation is remarkably robust to the

addition of other variables. The second row of the table contains

the basic "Bordeaux equation," while the third row shows the effect

on the regression of adding the temperature in September as an

additional variable. It is obvious that this variable does not

have a statistically significant coefficient and, indeed, in

further experimentation we have not found any other statistically

significant variables to add to the regression.

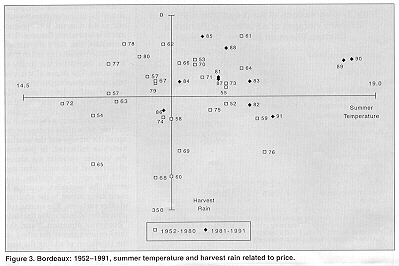

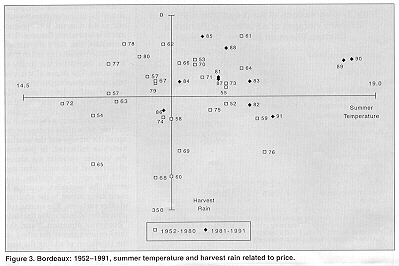

It is possible, of course, to predict the relative price at

which the new vintage should be sold as soon as the growing season

is complete. In fact, we have been doing this for several years

and publishing the results in the newsletter LIQUID ASSETS: The

International Guide to Fine Wines. The basic idea for these

predictions is displayed in Figure 3. Here we have added to Figure

2 the data for the vintages from 1981-1992. Two things are

immediately apparent from the figure. First, all but one of these

recent vintages (1986) was produced by a growing season that was

warmer than what is historically "normal." It is no accident that

many Europeans believe global warming may already be here! This

unusual run of extraordinary weather has almost certainly resulted

in a huge quantity of excellent, but immature red Bordeaux wine.

Second, the weather that created the vintages of 1989 and 1990

appears to be quite exceptional by any standard. Is it appropriate

to predict that the wines of these vintages will be of outstanding

quality when the temperature that produced them is so far outside

the normal range? Before making the prediction for 1989 we did, in

fact, turn to Professor Lincoln Moses (of Stanford University) for

informal advice. Moses suggested two informal tests. (a) Would

the last major "out of sample" prediction have been correct? The

idea here is to use the past to indirectly test the ability of the

relationship to stretch beyond the available data. In fact, the

last major "out of sample" prediction for which all uncertainty has

been resolved is the vintage of 1961, which had the lowest August-

September rainfall in Bordeaux history. Just as the unusual

weather predicted, the market (see Table 1), and most wine lovers,

have come to consider this an outstanding vintage. (b) Is the

warmth of the 1989 and 1990 growing seasons in Bordeaux greater

than the normal warmth in other places where similar grapes are

grown? The idea here is to determine whether the temperature in

Bordeaux is abnormal by comparison with grape growing regions that

may be even warmer. In fact, the temperature in 1989 or 1990 in

Bordeaux was no higher than the average temperature in the Barossa

Valley of South Australia or the Napa Valley in California, places

where high quality red wines are made from similar grape types.

Based on these two informal tests, we are convinced that both

the 1989 and 1990 vintages in Bordeaux are likely to be

outstanding. Many wine writers have made the same predictions in

the trade magazines. Of course, it is still too early to determine

whether the wines will fulfill their promise.

4. Market Inefficiency

It is natural to inquire as to the prices at which the wines

listed in Table 1 were sold when the wines were first offered on

the market. In particular, were the relative prices of the young

wines good forecasts of the relative prices the mature wines now

fetch? It is difficult to answer this question because the young

wines were all sold in different time periods and at prices that

are not generally known. Instead, we have explored a closely

related question: Were the relative prices of the vintages when

they were first sold in the auction market good forecasts of the

relative prices of the mature wines? And were the prices of the

young wines, viewed as forecasts of the prices of the mature wines,

as good as the predictions made using the data on the weather

alone?

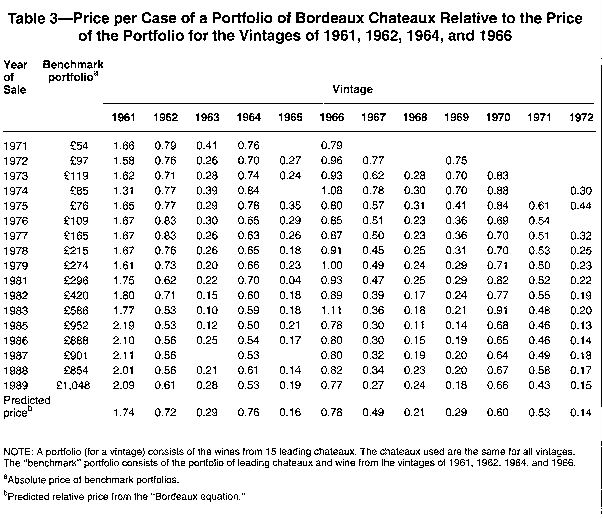

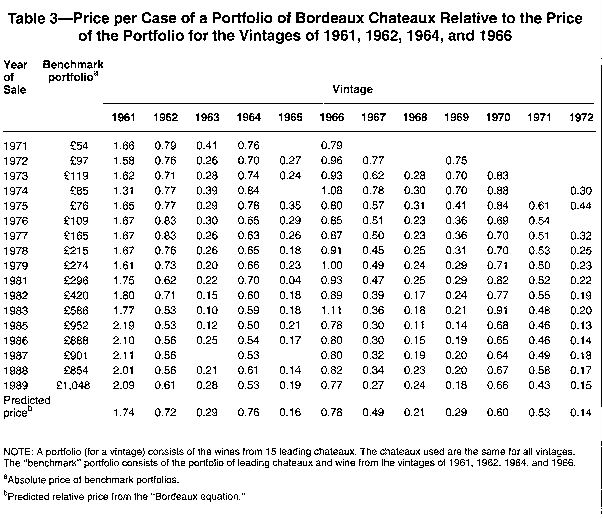

Table 3 reveals the answer to both of these questions. In

this table we have listed, for each calendar year from 1971-1989,

the price of the portfolio of wines from each vintage relative to

the price of the portfolio of wines from the 1961, 1962, 1964, and

1966 vintages.

The benchmark vintage portfolio is a simple average

of the 1961, 1962, 1964 and 1966 vintage indexes. The second

column gives the value of the benchmark portfolio in pounds

sterling in the year indicated, and provides a general measure of

the overall inflation in wine prices in the London auction markets.

The entries for each of the vintages in the remaining columns are

simply ratios of the prices of the wines in each vintage to the

benchmark portfolio in column 1 of the table. The 1961, 1962,

1964, and 1966 vintages were selected for the benchmark because the

weather data in Figure 2 predict they would be good, and the wines

from these vintages are, no doubt as a consequence, still widely

traded. The vintages that are studied in the table include all

those between 1961 and 1972. Listed in the bottom row of the table

is the predicted relative price of the vintage as taken from the

"Bordeaux equation" in Table 2.

The data in Table 3 confirm two remarkable facts. First, most

of these older vintages began their lives in the auction markets at

prices which are far above what they will ultimately fetch. For

example, the bottom row of the tables indicates that, based on the

weather, the wines of a vintage like 1967 would have been expected

to sell for about one-half the price of an average of the wines

from the 1961, 1962, 1964 and 1966 vintages. In fact, the wines

entered the auction markets in 1972 at about 50% more than

expected, and slowly drifted down in relative price over the years.

Second, the predicted prices from the "Bordeaux equation," which is

fit from an entirely different set of data, are remarkably good

indicators of the prices at which the mature wines will ultimately

trade.

One interesting way to see the inefficiency in this market is

to compare the prices of the vintages of 1962, 1964, 1967, and 1969

in calendar year 1972. As the weather data in Figure 2 indicate,

and the prediction in the bottom row of Table 3 confirms, we should

have expected (in 1972) that the 1962 and 1964 vintages would sell

for considerably more than the vintages of both 1967 and 1969. In

fact, in 1972 these four vintages fetched nearly identical prices,

in sharp contrast to what the weather would have indicated. By

around 1979 the prices of the 1969s and 1967s had fallen to around

what would have been predicted from the weather.

It is apparent from Table 3 that most vintages are "over-

priced" when the wines are first offered on the auction market and

that this state of affairs often persists for ten years or more

following the year of the vintage. The over-pricing of the

vintages is especially apparent for those vintages which, from the

weather, we would predict are the poorest. This suggests that, in

large measure, the ability of the weather to predict the quality of

the wines is ignored by the early purchasers of the wines.

An interesting recent example of this phenomenon is the 1986

vintage. As Figure 3 indicates, this is a vintage that, based on

the weather, we should expect to be "average." Compared to the

other vintages of the last decade, this vintage should fetch a

considerably lower price. In fact, the vintage was launched with

great fanfare as among the finest two vintages of the decade. The

wines were sold at similar, and sometimes higher, prices to initial

buyers than the wines of the other vintages of the past decade.

The enthusiasm for these wines has dampened somewhat because they

have not fetched auction prices higher than those of the other

vintages in the decade. We should expect that, in due course, the

prices of these wines will decline relative to the prices of most

of the other vintages of the 1980s.

5. Conclusion

Why does the market for immature red Bordeaux wines appear to

be so inefficient when the market for mature wines appears to be so

efficient? We think there may be several related explanations.

The current Bordeaux marketing system has the character of an

agricultural income stabilization system, and this may be its

purpose. Complete income stabilization for the growers would

require that the price of the young wines be inversely related to

the quantity produced, and independent of the quality. Although

the actual pricing of young Bordeaux wines falls short of this

ideal, it is clearly closer to it than would occur if purchasers

used the information available from the weather for determining the

quality of the wines. The producers do attempt to raise prices

when crops are small, despite the evidence that the quantity of the

wines (determined by the weather in the spring) is generally

unrelated to the quality of the wines. Moreover, it is common for

the proprietors to claim that each vintage is a good one,

independent of the weather that produced it. Indeed, there is no

obvious incentive for an individual proprietor to ever claim

anything else!

A more fundamental question arises about the motives of the

early purchasers of the wines. Why have they ignored the evidence

that the weather during a grape growing season is a fundamental and

easily measured determinant of the quality of the mature wines?

And will they continue to do so as the evidence for the

predictability of the quality of new vintages accumulates?

REFERENCES

Haraszthy, A. Grape Culture, Wines, and Wine-making, New York:

Harper & Bros., 1862.

Liquid Assets: The International Guide To Fine Wines, 169 Nassau

St., Princeton, NJ 08542, various issues.

Penning-Rowsell, Edmund. The Wines of Bordeaux, Fifth Edition, San

Francisco: The Wine Appreciation Guild, 1985.

Return to previous page

Go to the data and regressions

As

a result, the regression equation is remarkably robust to the

addition of other variables. The second row of the table contains

the basic "Bordeaux equation," while the third row shows the effect

on the regression of adding the temperature in September as an

additional variable. It is obvious that this variable does not

have a statistically significant coefficient and, indeed, in

further experimentation we have not found any other statistically

significant variables to add to the regression.

As

a result, the regression equation is remarkably robust to the

addition of other variables. The second row of the table contains

the basic "Bordeaux equation," while the third row shows the effect

on the regression of adding the temperature in September as an

additional variable. It is obvious that this variable does not

have a statistically significant coefficient and, indeed, in

further experimentation we have not found any other statistically

significant variables to add to the regression.